Rapid and safe evaluations of LLMs: how clinical simulation closes the evidence gap

Rapid and safe evaluations of LLMs: how clinical simulation closes the evidence gap

Clinical simulation is an ideal methodology for robustly evaluating clinician-facing, LLM-based technologies before they are deployed at scale.

In this piece, we explore why robust evaluation is essential for LLM-based technologies and highlight why clinical simulation offers a particularly well-suited methodology for assessing their clinical utility before large-scale deployment.

Why do healthcare AI solutions need strong evidence?

In our white paper on evidence generation for AI in healthcare, we argued that it was essential to build trust in these solutions through robust evidence generation (1).

These principles remain as relevant as ever, but the recent surge of interest in large-language models (LLMs) has introduced both new opportunities and new risks that demand careful consideration.

LLMs have become a focal point of discussion with their potential applications in healthcare ranging from ambient scribes to clinical decision support tools.

Concurrently, concerns about their reliability and safety within high-stakes medical contexts have underscored the urgency of developing rigorous approaches to their evaluation.

What types of evidence are required?

From a regulatory perspective, the initial evidence required to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of digital health solutions typically comprises two components (2,3).

The first is analytical validation, that requires the manufacturer to demonstrate that the device works technically and produces accurate, reliable and reproducible outputs under defined conditions.

The second is clinical validation, which is used to demonstrate that the device achieves its intended purpose in practice, showing safety, performance and effectiveness in a real-world healthcare context.

While regulatory approval is essential, it does not guarantee sustained success or uptake within healthcare systems. One key factor to consider is demonstrating financial value through health economics. This can be done from early on, through financial forecasts and return-on-investment (ROI) calculations, to widespread adoption via cost-effectiveness analysis.

Once on the market, generating real-world evidence (RWE) is critical to win the confidence of health systems, clinicians, and users. This includes data from diverse settings and user research to ensure solutions fit into existing workflows. In our previous white paper, we described this as solution evidence: the body of proof that extends beyond regulatory compliance into adoption, scale and trust (1).

What are the unique evidence requirements of LLMs?

The unique challenges posed by the LLM development process require a deeper understanding of how these generative technologies are applied and evaluated in the clinical context.

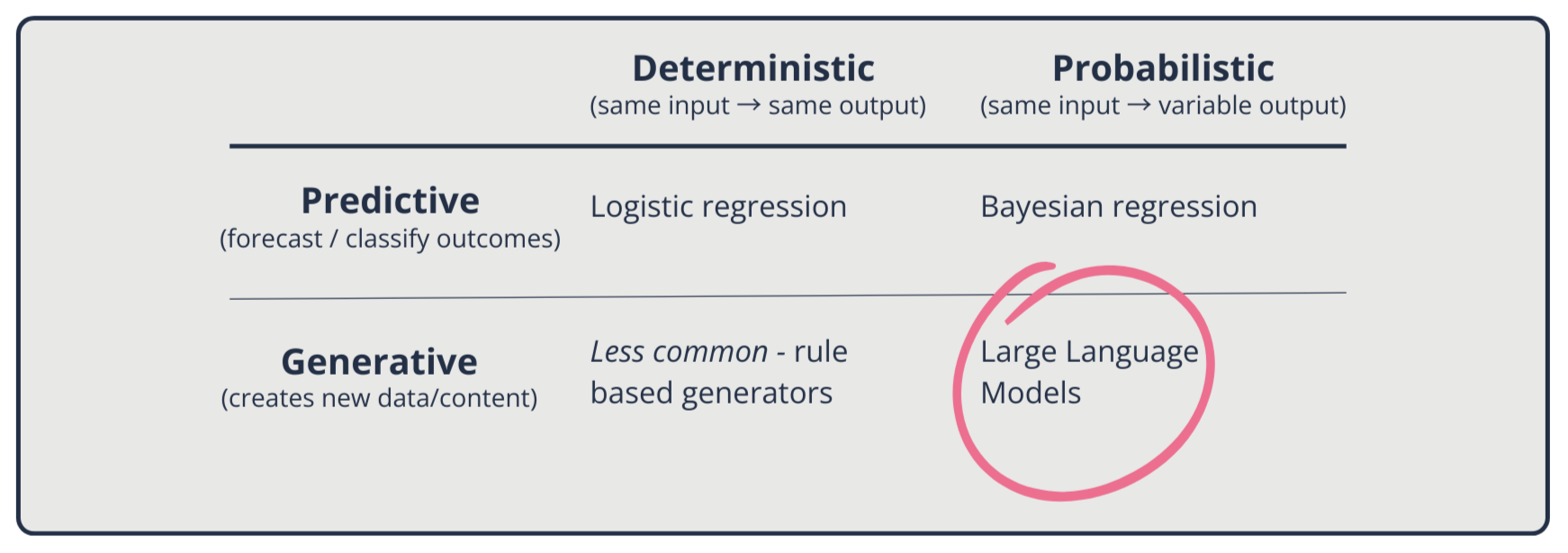

LLMs mark a departure from earlier statistical, rule-based, and machine-learning approaches in healthcare. Previously, those models were primarily predictive and designed to classify, forecast or estimate risk (4).

Many of the earlier models are deterministic: given the same input, they will reliably produce the same predicted outcomes (e.g. Logistic regression*). Others are probabilistic (e.g. Bayesian models**), which capture uncertainty but remain fundamentally predictive.

By contrast, LLMs are generative (4). Rather than predicting a label or outcome, they construct new text probabilistically based on learned statistical patterns. This generative capacity makes them versatile but also introduces new risks, such as uncertainty, variability, and non-reproducibility.

* Logistic regression is a simple method that learns from data to estimate the chance of a yes/no outcome (e.g., will this patient need follow-up?), producing a probability between 0 and 1; you can then set a cutoff to turn that probability into a decision.

** Bayesian regression is a way for AI to learn from both past knowledge and new data to make predictions, while also telling you how confident it is in those predictions. In short: it doesn’t just say what might happen, it shows the chance of each outcome.

This generative quality introduces a unique challenge known as hallucinations, where an LLM produces information that is coherent and persuasive, but factually incorrect. Crucially, hallucinations are not simple “bugs”; they arise from the way LLMs are trained and optimised (5).

In consumer contexts, occasional inaccuracies may be tolerable. However, in healthcare, they carry significant risks, including misleading clinicians, undermining trust, and directly harming patients (6).

Recent evaluations demonstrate these concerns. Despite achieving high scores on medical licensing exams, models often perform inconsistently in realistic clinical decision-making scenarios by failing to follow guidelines, misinterpreting results, or showing sensitivity to seemingly trivial changes in input (6). Furthermore, the impact of LLMs can extend beyond just incorrect text by shaping workflows and influencing decision-making (7).

What is the challenge with evidence generation for AI solutions and LLMs in particular?

Digital health solutions, including AI-based ones, require appropriate evidence-generation approaches that account for the unique features of software compared to other healthcare products, such as pharmaceuticals.

Our 2020 paper in Nature Digital Medicine, Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions—A call for innovative evidence generation approaches, identified several issues with traditional evidence generation methods, including:

The time required is incompatible with the fact that software changes over time, with new versions continually released.

The high resource requirements and costs are often incompatible with the budgets of small- and medium-sized companies, which constitute the majority of the digital health sector.

Why is clinical simulation a crucial evidence generation method for LLMs?

Clinical simulation can help generate robust evidence rapidly and at a reasonable cost, as highlighted in our above-mentioned paper.

The unique strengths of clinical simulation as an evidence generation method for LLMs include:

Speed: This is one of the most important advantages, as simulations can be completed in weeks or months, rather than the years required for large-scale clinical trials (8). This makes them particularly well-suited to the rapid, iterative cycle of technology development, where solutions may evolve multiple times within the typical duration of an RCT.

Cost: Another distinct advantage is the ability to deliver robust evidence at a fraction of the cost of conventional studies.

Patient safety and data privacy: By relying on synthetic data and clinical vignettes rather than real patient data, simulations intrinsically remove the risk of patient harm and data privacy concerns.

Equity: The use of synthetic data means that high-risk, marginalised or underrepresented groups, who are frequently excluded from traditional studies, can now be included without privacy concerns. An example is PATH’s recent initiative, which developed clinical vignettes in three African countries to ensure that the evaluation of LLM-based technologies considers locally relevant contexts and populations (9).

Acceptability by regulators: An eDelphi consensus study led by Prova Health’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr Saira Ghafur, at Imperial College London concluded that simulation-based studies are considered sufficient evidence for regulatory approval of Class I and Class IIa medical devices (10).

Reduction of deployment risks: By enabling earlier, less expensive evidence generation, simulation helps de-risk deployment and accelerate the safe integration of these tools. For LLM-based solutions, where context and unintended consequences are central challenges, clinical simulation provides a uniquely powerful bridge between technical validation and real-world evidence.

Ability to generate solution evidence: By placing technologies directly in the hands of end users, it provides immediate feedback on usability and trust, helping product teams refine features earlier in the development cycle. Clinical simulation also enables evaluators to study the sociotechnical interactions, including how clinicians respond to them, how they integrate into workflows, and how they may influence clinical decision-making.

That said, clinical simulation is not always the most appropriate method. It is particularly valuable when there is direct interaction between users and the technology, such as clinical decision support tools or ambient scribes.

Technologies that operate largely in the background, such as automated billing, coding, or other administrative tasks, may require alternative methods.

How does clinical simulation evaluate LLMs in practice?

Clinical simulation involves placing clinicians (or other end users) in realistic, high-fidelity scenarios to examine how a digital health technology would function in practice.

These simulations often utilise synthetic patient data to recreate clinical environments as closely as possible, ensuring that a tool is assessed in the same context in which it will be used. To help conceptualise this, we have created the hypothetical example below.

Testing a clinical decision support through simulation

Imagine a company is developing an LLM-powered clinical decision support tool that helps doctors manage patients with multiple, complex, long-term conditions.

In a clinical simulation, doctors could work through 20 realistic, synthetic patient cases. Each doctor would review half the cases using the tool and half without, under timed, real-world conditions.

You could then compare the two sets of decisions against expert-defined “gold-standard” care plans, evaluating how accurate, safe, and appropriate the recommendations were, as well as how long they took.

This setup would show whether the tool genuinely supports better, faster, and safe decisions before it is tested in real clinics or affects patient care.

Case study: evaluating navify Clinical Hub for Oncology through clinical simulation

At Prova Health, we recently utilised this method to evaluate navify Clinical Hub (nCH) for Oncology, which has an LLM-based summarisation tool developed by Roche.

Within four months, from study design and recruitment to simulation and analysis, we were able to deliver a full evaluation across four major markets (the US, UK, Spain, and Singapore).

Board-certified (consultant) oncologists (n=26) reviewed ten synthetic breast cancer cases and prepared summaries for tumour board (or MDT) meetings. Using the solution, clinicians were able to generate solutions more quickly (415 seconds vs. 527 seconds, p<0.001). The summaries also demonstrated greater completeness (p<0.001), while maintaining accuracy and conciseness.

Qualitative feedback from participants reinforced these findings, with more than 90% reporting that nCH would save them time, and almost 90% saying they would recommend it to a colleague.

This study was accepted at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, demonstrating both the clinical relevance of the results and the credibility of simulations as a method for evaluating emerging LLM-based technologies (11).

So what?

LLM-based technologies are poised to become a crucial component of healthcare delivery. But their safe deployment depends on robust evaluations.

By capturing both technical performance and the sociotechnical dynamics of real clinical practice, clinical simulation offers developers, regulators, and health systems a faster, more cost-effective, and more equitable way to de-risk innovation.

Want to build trust in your LLM solution and get it into clinical use faster?

Clinical simulation is fast, credible, and rooted in real-world practice.

If you’re developing an AI tool and want to explore how innovative evidence generation can support your growth ambitions, get in touch with us at hello@provahealth.com.

References

Patel M, Popescu M, Jangam S, Conroy D, Fontana G, Ghafur S. Trust through evidence: Evidence generation for AI solutions in healthcare [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.provahealth.com/white-papers-list/trust-through-evidence-white-paper

Medical Device Coordination Group. MDCG 2020-1 Guidance on clinical evaluation (MDR). Perform Eval IVDR Med Device Softw. 2020;2020–09.

FDA. Software as a Medical Device (SAMD): Clinical Evaluation - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff [Internet]. U.S. Food & Drug Administration; 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/100714/download

Caballar R. Generative AI vs. predictive AI: What’s the difference? | IBM [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/generative-ai-vs-predictive-ai-whats-the-difference

Kalai AT, Nachum O, Vempala SS, Zhang E. Why Language Models Hallucinate [Internet]. arXiv; 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 24]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2509.04664

Hager P, Jungmann F, Holland R, Bhagat K, Hubrecht I, Knauer M, et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nat Med. 2024 Sept;30(9):2613–22.

Mehandru N, Miao BY, Almaraz ER, Sushil M, Butte AJ, Alaa A. Evaluating large language models as agents in the clinic. Npj Digit Med. 2024 Apr 3;7(1):84.

Guo C, Ashrafian H, Ghafur S, Fontana G, Gardner C, Prime M. Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions—A call for innovative evidence generation approaches. Npj Digit Med. 2020 Aug 27;3(1):110.

PATH. Designing Trust: A step-by-step guide for applying Human-Centered Design principles in creating benchmarking datasets for training and testing large language models to be used in clinical decision support [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 24]. Available from: https://www.path.org/our-impact/resources/designing-trust-a-step-by-step-guide-for-applying-human-centered-design-principles-in-creating-benchmarking-datasets-for-training-and-testing-large-language-models-to-be-used-in-clinical-decision-support/

O’Driscoll F, O’Brien N, Guo C, Prime M, Darzi A, Ghafur S. Clinical Simulation in the Regulation of Software as a Medical Device: An eDelphi Study. JMIR Form Res. 2024 June 25;8:e56241.

Halligan J, Patel M, Obery G, Lajmi N, Dorge A, Sharma A, et al. Evaluating the efficiency and quality of clinical summaries produced by a large language model (LLM). J Clin Oncol. 2025 June;43(16_suppl):e13601–e13601.

About the author - Dr Gareth Obery, MBChB, MSc

Gareth is a Digital Health Consultant at Prova Health, specialising in evidence generation, market access, and health economics. He has led clinical simulation studies for organisations ranging from start-ups to multinational corporations. A South African-trained medical doctor, he holds a Master’s in Applied Digital Health from the University of Oxford, where his research compared statistical and machine learning methods for risk prediction.